How can I . . . understand more about the fight or flight response?

I remember my manager sending me to assess my very first murderer. I was a young, trainee psychologist, and as I sat opposite this man (let’s call him Sam), who was reaching the end of his tariff of a life sentence, I recall being fascinated by his hands. He sat with them folded neatly in front of him, on the desk. His nails were short and clean. His hands looked strong and all I could think was that those hands had ended somebody’s life. It was a defining moment at the start of my career, and as I talked to this polite, softly-spoken man, who was only ten years older than me, I tried to picture him as the teenager who had battered another man to death with those hands and a wooden chair. I can still recall the description of the wooden chair, being found in splintered pieces, due to the force used in the assault.

Obviously, I had read Sam’s files and knew the details of what had happened. Sam spoke calmly and eloquently about the terror and rage that overcame him that night, and the absolute belief at that time that he had to take action in order to save himself. You see, his victim was an older man who had ‘kindly’ taken this vulnerable teenager under his wing from the streets and after a couple of weeks, decided to make a pass at Sam. Sam explained that the man would not take no for an answer and “I saw red. I couldn’t remember what happened for a while, but I admitted what I’d done because I know I killed him.” Sam said he deeply regretted his actions and as we spoke further about his offence I believed his regret to be genuine.

All about Sam

Sam had no previous offences, not even theft or drug possession which was surprising for someone who had lived on the streets for a couple of years. He was described as a ‘model prisoner’ and seemed to be well-liked by both staff and other prisoners. So what happened on the day of the offence? A little bit of background information about Sam revealed that his parents had separated after a highly volatile relationship and a number of violent acts which were witnessed by Sam from being a baby. His father would physically beat him and his siblings, and when his mother eventually ended their relationship, this was followed by a string of other short-lived relationships with different men, some of whom would sexually and physically assault him and his mother. Sam was eventually removed into the care system, however he was so traumatised by then that his placements with fosterers broke down and he was placed in a children’s home. He was sexually abused in this home by one of the male carers. He frequently ran away from the home until one day, he could not be found and so he was left to live on the streets. Sam was thirteen.

By the time he met his future victim, Mr X, he was fifteen-years old and had ‘survived’ through the help of various charities, hostels and small cash-in-hand jobs. He met Mr X through one of these jobs and Mr X offered him friendship, food and eventually his sofa for a few nights, as it was getting cold outside. On the day of his offence, they were playing a card game and having a beer when “all of a sudden he got up and walked behind me. He reached over my shoulders and touched me and tried to kiss me from the back and I shrugged him off. He laughed and got me in a bear hug and then I lost it.”

Role of the Amygdala

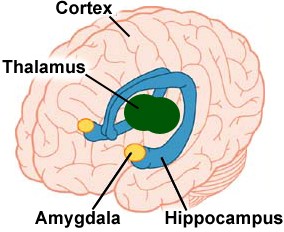

As an inexperienced, trainee psychologist, I didn’t know as much then as I do now about trauma, the brain and the role of the amygdala. The amygdala is a small area at the centre of the brain which dictates our fight or flight response. When we experience a situation that is threatening to us, the amygdala takes over in the way that we would expect a bodyguard to. It orders us to take action to save ourselves in the threatening situation by running away, fighting or sometimes, freezing. These are entirely automatic responses during which the rational, thinking parts of our brains are shut-down. There is no time to reason, weigh up the pros and cons of action or take advice in these types of situations. It is literally in matters of life or death that we have to respond in this way. If we had paid a bodyguard thousands of pounds to keep us safe, we wouldn’t be too impressed if his reaction to the approach of knife-wielding attacker was to pause to consider the safest course of action. We’d expect him to take immediate, automatic action to keep us safe by getting us out of the way and diffusing the threat.

Now, Sam wasn’t a career criminal. He wasn’t a sadist, or a manipulative con-man, planning to fleece Mr X. He was a frightened, abused child who had suffered unimaginable levels of trauma already in his life. On the day of the offence, his amygdala knew that when faced with this familiar, threatening situation of an older, stronger man making sexual advances, he needed to take action to save himself. He was physically unable to run away so he fought. And fought to the death of his attacker. Sam said “I know I over-reacted and I shouldn’t have. There was no need for me to kill him. I should’ve stopped but I didn’t know what I was doing then.” This is no surprise, as the thinking part of his brain was ‘shut-down’ by his amygdala. The amygdala tells us, and would have told Sam to do whatever he needed to, in order to be safe. Sam’s amygdala would not have told him to carefully push the man away so he could then escape that situation.

Implications

Have you ever seen one of those slasher movies in which a young, teenage girl is being chased by a knife-wielding maniac? Sometimes, she’ll be cornered and have nowhere to run, so she fights back. This often annoys me as it’ll take the form of her hitting him, disabling him for a while and then he’ll usually recover in time to chase her again and kill her. Well, all good bodyguards and soldiers know that the threat to life has to be neutralised if we want to survive. If the attacker can get up, you are not safe. Our amygdala knows this too. Sam’s amygdala knew this.

There is no controlling that primitive part of the brain. Prisoners have told me that they often learn the hard way to choose their victims carefully, as they have no way of knowing if the person they’re about to rob could harm them. The lone, small female might look an easy target to rob, but if her stride is confident and she is vigilant to her surroundings, she could be holding her keys in her hands and through fear she could repeatedly strike out and cause serious injury before running away.

Consider sexual offenders who target strangers and will often choose those they view as vulnerable, through size, intoxication or age. They don’t want to run the risk of choosing a victim who will fight as a result of fright and potentially cause them serious harm (unless they are a rare but dangerous type of sexual offender who enjoys this response).

Consider youths who now often carry knives so are at an increased risk to others, as well as more likely to be stabbed themselves. Why is this? If they are attacked by other youths, and have to fight to save themselves, their amygdala will tell them to do whatever is necessary to save themselves. So that knife in their pocket comes in useful, but can easily be dropped and used by their attacker who is also fighting for their lives.

Consider the ‘Killer Clown’ craze, in which it seems so harmless and funny to dress up and frighten unsuspecting members of the public. This will end badly when a joker targets a particular mother in the park with her children. Does the clown really want to take a chance that the mother will turn and run away with her screaming children? There is just as much likelihood of her acting in defence of her frightened children by attacking the clown herself and potentially ‘neutralising’ the threat so he won’t be a risk to them.

Over the years as a forensic psychologist, I’ve sat across many desks with people whose hands have carried out atrocious acts of violence towards other people. Not all the result of the fight-or-flight response, but that’s the subject of another post. Still, I’ll never forget Sam and his hands.

All names and identifying details of clients have been changed to protect confidentiality